This Week in Grateful Dead History: December 31, 1978 (Listen Now)

The storyteller makes no choice, soon you will not hear his voice; his job is to shed light and not to master.

By The Deadhead Cyclist

For Week

1

It is often said that all good things must come to an end. But what is equally true – and far more promising – is that every ending offers the potential for a beginning. In that spirit, this literary trip around the sun begins at the end: the end of a year, the end of a beloved venue, the end of an era.

For many Deadheads, the Grateful Dead and New Year’s were synonymous. I mean, what better way to celebrate life – both its endings and its beginnings – than to see the band on New Year’s Eve? The Dead were famous for their New Year’s shows, and played twenty-one times at the dawn of a new year. Six of those shows took place at the Winterland Ballroom, an erstwhile ice skating rink which became a storied rock music venue with a capacity of some 5000. Sadly, Winterland was shuttered after one final New Year’s concert, known affectionately as “The Closing of Winterland.” This historical context, coupled with its eight-hour length – including performances by the Blues Brothers and the New Riders of the Purple Sage – easily makes this the most famous of the Dead’s New Year’s shows, and the Deadhead Cyclist’s inaugural choice for T.W.I.G.D.H. (This Week In Grateful Dead History).

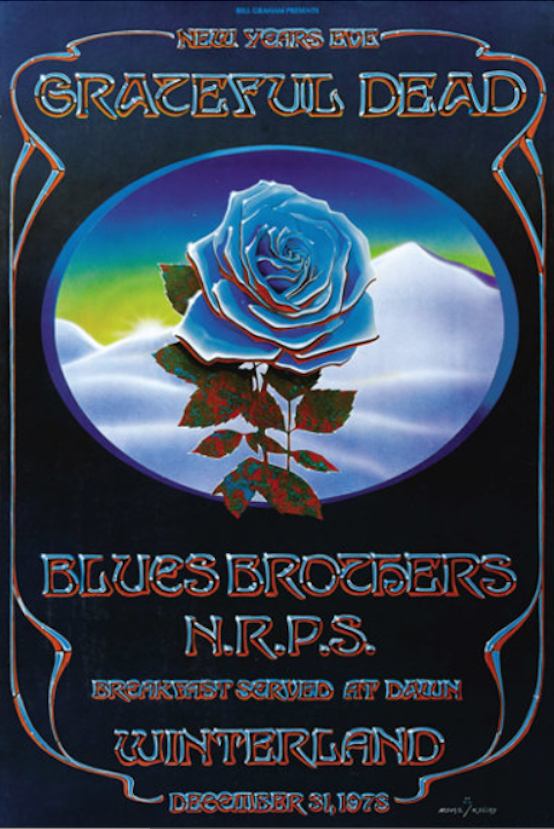

Many have referred to seeing a Grateful Dead concert as a religious experience. If so, Winterland was the Sistine Chapel of all the venues the Dead played. But whereas the latter was adorned with the High Renaissance art of Michelangelo, the halls of Winterland were bedecked with the psychedelic poster art of Stanley “Mouse” Miller, Rick Griffin, Wes Wilson, Alton Kelley, Victor Moscoso, and many others. Having seen both I have a strong preference for the latter, as both a gallery and house of worship. Commonly known as the “Blue Rose,” the poster for the 12/31/78 show was a collaboration by Alton Kelley and Stanley Mouse.

Originally known as the New Dreamland Auditorium, the venue opened in 1928. The name was changed to Winterland in the late 1930s, but it wasn’t until 1966 that legendary concert promoter Bill Graham turned Winterland into a rock palace with a show featuring the Jefferson Airplane and the Paul Butterfield Blues Band. From the Rolling Stones and The Doors to the Allman Brothers and Led Zeppelin, the list of artists who performed under the flickering lights of the famous Winterland “mirror ball” reads like a roll call of inductees to the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.

But no matter who was on the Winterland stage, the Grateful Dead’s “Skull and Roses” logo proudly hung in the background. The Dead played Winterland 59 times, more than any venue other than the Oakland Coliseum Arena. It was undisputedly their “home court” until the final buffet breakfast was served on the morning of January 1st, 1979.

Historic nostalgia aside, there’s one overriding reason this concert is my choice for the best New Year’s show of all time: the music. I discovered an unexpected highlight of the show through my wireless earbuds one glorious desert afternoon while riding the trails adjacent to Blue Diamond, Nevada. The second set begins with a kick-ass Samson and Delilah, and then gives us a chance to catch our breath with a lovely Ramble on Rose. But what really got me off was a tune that had never before been one of my favorites: I Need a Miracle. This eleven-plus minute version starts strong and never lets up, with surprisingly extended jamming, segueing into outstanding versions of Terrapin Station and Playing in the Band. In my cycling-expanded frame of mind, one line in Terrapin reverberated:

The storyteller makes no choice, soon you will not hear his voice; his job is to shed light and not to master.

Consider the possibility that your thoughts are merely a story you are telling yourself that may or may not be completely accurate. We are all storytellers, just as capable of telling a story to ourselves as we are to others.

The word, “storyteller,” reminded me of the day in 2002 when I had the honor of interviewing Miguel Ruiz for a piece I was writing for Boulder Weekly. Ruiz is a world-renowned shaman and author of one of my favorite books, “The Four Agreements.” We had a spirited telephone conversation during which he enlightened me on topics ranging from social evolution to storytelling:

“Humans are storytellers. It is our nature to make up stories, to interpret everything we perceive. Without awareness, we give our personal power to the story and the story writes itself. With awareness, we recover the control of our story. We see we are the authors and if we don’t like our story, we change it.”

It’s intriguing to recognize the Storyteller character in Terrapin Station as being cut out of the same cloth as the “storytellers” Ruiz refers to in his native Toltec tradition. In both examples, we are encouraged to understand the stories we hear as interpretations, and not necessarily truth. In this way we become an observer of the story and identify it as a source of insight, rather than allowing it to determine the choices we make.

In the Terrapin story, we’re presented with two characters, a sailor and a soldier, who face temptation in the persona of a beautiful girl (“eyes alight with glowing hair/all that fancy paints as fair”). The heroes of our story face a choice with respect to this temptation that involves certain risks (“uncertain pains of hell”), and they are dared to be courageous (“I will not forgive you, if you will not take the chance”). The sailor and the soldier choose differently, each remaining true to his purpose. As for the Storyteller, he offers no judgment, allowing us to be the arbiters (“You decide if he was wise”).

The lesson is clear: The stories we hear are most valuable with respect to the light that they shed. Ultimately, we must make our own decisions, as we are the ones who will live with the consequences. In the famous Marvin Gaye tune, “I Heard it Through the Grapevine,” we are advised, “Believe half of what you see and none of what you hear.” Expanding upon that notion to include our thoughts reminds me of a well-known bumper sticker that says:

Consider the possibility that your thoughts are merely a story you’re telling yourself that may or may not be accurate, given your personal agenda, whatever that might be.

As an aging cyclist, I regularly struggle with the stories I tell myself about my increasing limitations. For example, I might tell myself, “When I was younger I could ride steep, rocky trails, but I’m too old to do that now.” This story may or may not be true, but if I believe it without examining its veracity, I’ve surrendered my personal power to that account and allowed the story to write itself.

Instead, I can reclaim control of my narrative and rewrite it: “I’m older now, and it’s becoming harder for me to ride steep, rocky trails, so I’m committed to working harder to stay in shape so that I can continue to enjoy my passion for mountain biking.”

There’s a parallel between this challenge, and the one implicit in Grateful Dead lyricist Robert Hunter’s tour de force, Terrapin Station. In this brilliant piece of storytelling, Hunter introduces us to a mythical place: Terrapin. This is no ordinary place, but one that beckons to us in the way that it represents our highest selves. To get there requires the invitation of inspiration (“Inspiration, move me brightly”) and the rejection of despair (“Hold away despair”). And it is a place that is unique to every individual, as each one of us must follow a customized path to achieve it (“Some rise, some fall, some climb, to get to Terrapin”).

As we begin this journey around the sun together, understand that the Deadhead Cyclist is merely your guide. My stories of cycling, career, baseball, parenting, intuition, perseverance, ego death, truth and love are intended to shed light, and not necessarily to provide a blueprint to follow. They contain the life lessons I’ve learned, but at the end of the day, you must write your own story and learn your own lessons.

But beware: Living in a world of storytellers – and being one of them yourself – is a double edged sword. On one side is self-deception, while on the other there’s the potential for profound insight. Learning to distinguish between the two requires the slow and steady patience necessary to rise, fall, or climb to the place known, metaphorically, as Terrapin.

Whether on January 1st or any other day of the year, the time is ripe to examine the stories you tell about your life. My highest hope as the Deadhead Cyclist is that sharing my personal journey might be just the “headlight on a northbound train” to get you through the “cool Colorado rain.” All aboard!

Concert of the week in Grateful Dead history: December 31, 1978 (Listen Now)

Subscribe and stay in touch.