Concert of the week in Grateful Dead history: February 27, 1969 (Listen Now)

Solemnly they stated, “He has to die. You know he has to die.”

By The Deadhead Cyclist

For Week

9

Is there any more compelling storyline in the human experience than the knowledge of our inevitable death and our unique ability to contemplate it? Think about it. What other factor in your life has had a more profound impact on your behavior and experiences? Drawing a blank, huh?

My dog, Bella, just turned ten, which makes her about the same age as I am, biologically speaking. Just yesterday we were out on a walk and it occurred to me that she never gives a moment’s thought to the fact that she will probably die within the next few years. I, on the other hand, think about my death on a daily basis. Talk about “always awake, always around,” this aspect of our existence is as inseparable from who we are as the air we breathe or the rhythm of our heartbeat.

The inescapable reality of each human life – no matter where you live, who you were born to, what color your skin and eyes are, and regardless of what period of history you happened to drop into – is that how you live is inexorably connected to the way you confront your mortality. This may explain the Grateful Dead’s seemingly disproportionate focus on death. Perhaps more importantly, it sheds light on the astonishing size and devotion of the Deadhead community.

To the untrained eye, the name Grateful Dead appears to be an oxymoron, a figure of speech that describes the juxtaposition of seemingly self-contradictory elements. In fact, at Oxymoronlist.com there’s a page devoted to The Grateful Dead. But within the context of the band, do the words “grateful dead” belong in the same category as such classics as “clearly confused,” “only choice,” “growing smaller,” “civil war,” “awfully good,” or “deafening silence?”

According to the band the answer is a firm, “No.” It turns out, to the contrary, that Grateful Dead is a tautology, words placed together that mean the same thing – the opposite of an oxymoron. While it may seem like a bridge too far to place “grateful dead” in the same category as “arid desert,” “frozen ice,” “necessary requirement,” or “short summary,” upon further review it’s anything but an “over exaggeration.”

Although the story of how the band changed its name from The Warlocks to the Grateful Dead is well-known within the Deadhead community, perhaps the best account is presented in the wonderful 2017 documentary film, Long Strange Trip. It seems that Jerry was at Phil’s house discussing the need for a new name, when Jerry opened a Funk & Wagnall’s dictionary and, like the lightning bolt in the Steal Your Face logo (AKA, the “Stealie”), the words, “Grateful Dead” jumped off the page.

“It was, like, kind of, like, creepy. But I thought it was a striking combination of words,” Jerry reminisced in an interview used in the film. But calling the name, Grateful Dead, a “striking combination of words” falls short of explaining the perfectly tautological nature of the expression.

Grateful Dead biographer and publicist, Dennis McNally, brings us a little closer: “Grateful Dead, the expression, is not really about death. The stories are about karma. How you live your life and how you relate to other people. By confronting death you learn how to live.”

Bassist and founding member of the band, Phil Lesh, truly sends us off in the right direction: “Because (the concept, Grateful Dead) embraced all of the spiritual rebirth aspect of what we were trying to do, and what we had experienced at the Acid Tests. This is who we are. We are the Grateful Dead. We’re grateful to be dead because now we’re going to be born anew into this incredible world that we’re just glimpsing the edges. And it (the name Grateful Dead) was perfect.”

There I was at Winterland, dancing to the music of the Grateful Dead and tripping heavily on Windowpane, when my deep-seated insecurities intruded at the forefront of my consciousness. Suddenly, from out of nowhere, an unmistakable voice admonished me: “Nobody cares about you!”

One of the keys to understanding the perfect synergy of the words “grateful” and “dead” is to identify Phil’s reference to the acid tests as a clue and recall the essential nature of the psychedelic experience. The “Acid Tests” were a series of “happenings” hosted by author and countercultural icon, Ken Kesey, mostly in the San Francisco Bay Area during the mid-’60s, the primary purpose of which was the use of and advocacy for the psychedelic drug, lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD). And, of course, the Grateful Dead became an essential component of the Acid Tests (and vice versa).

The fascination with LSD and the psychedelic experience during the “Hippie Movement” had to do with a general sense of dissatisfaction with mainstream culture, and the spiritual awakening that was available to those who used the drug. (And, of course, in a classic example of “the more things change, the more they stay the same,” these same sentiments continue to be felt today.) Users report a profoundly expansive experience, often accompanied by intense joy or euphoria, a deep appreciation for life, and a sense of belonging or oneness with the universe. This last sensation is referred to by psychologists as “Ego Dissolution.”

According to a recent article in Live Science, “Why People ‘Lose Themselves’ When They Take LSD,” individuals under the influence of LSD, “may feel as if the boundary that separates them from the rest of the world has dissolved, as if they are connected with everything.” The article refers to a recent study which suggests that there is a “neural mechanism” for Ego Dissolution which offers clues to how our brains function. This phenomenon, better known as “Ego Death” within the context of the Acid Tests, became a fundamental component of the Grateful Dead community.

If you’ve ever been on the floor (often referred to as “the pit”) at a Grateful Dead concert, or if you’ve seen video of the crowd immediately in front of the stage at, say, Winterland during the ’70s, it’s easy to observe the psychedelic energy flowing. I, myself, had an Ego Death moment while tripping on acid at that very longitude and latitude during the final shows of the Dead’s famous Spring ’77 tour. Having moved from my hometown of St. Louis Park, Minnesota at the vulnerable age of 12, I had become even more self-conscious than the average pre-teen when I was told by one of my new classmates at a junior high school dance, “You dance funny.” Apparently, kids in Minnesota danced differently than kids in California, but at this vulnerable age this was devastating, and it became a source of anxiety any time I found myself in a situation where people were dancing.

So, there I was at Winterland, age 22, dancing to the music of the Grateful Dead and tripping heavily on Windowpane, when my deep-seated insecurities intruded at the forefront of my consciousness. In a sudden state of paranoia, I looked around to see if anyone was watching when suddenly, from out of nowhere, an unmistakable voice admonished me: “Nobody cares about you!” As these powerful words echoed through my head and traveled downward into my heart, I understood their meaning: I was being instructed to get over myself and let go of the idea that anyone actually cared how I danced.

This customized psychedelic Ego Death experience has had a lasting effect on me throughout my life in ways too numerous to mention. So, if just one Ego Death moment changed the course of my life, imagine the influence hundreds, even thousands of acid trips had on Jerry, Bob, Phil, Bill, Mickey, and the rest of the Grateful Dead machine. This subordination or surrender of the individual to achieve a union with the greater collective became the central guiding principle of the music, the messages and the very soul of the Grateful Dead.

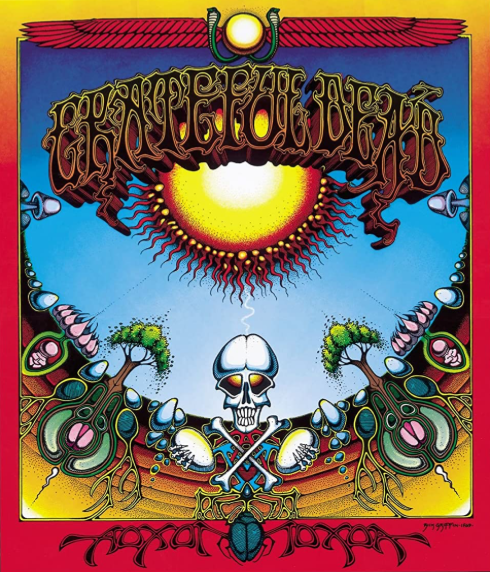

This is more than evident in my pick for T.W.I.G.D.H., the 2/27/69 show at the Fillmore West in San Francisco. This legendary show features most of the material on the Dead’s overtly LSD-inspired third album, Aoxomoxoa, the front cover of which dramatically depicts the Ego Death concept with classic psychedelic visuals. What is perhaps most noteworthy about this show is that the performances of Dark Star and St. Stephen are none other than the ones featured on the band’s first live album, Live Dead.

After opening the show with Good Morning Little Schoolgirl, from the Dead’s first album, and Doin’ That Rag, from Aoxomoxoa, the band went back to the Anthem of the Sun album and performed the Cryptical Development Suite, which includes the haunting, repetitive declaration, “He has to die. You know he has to die,” which then, tellingly morphs into:

He had to die, oh, you know he had to die.

Given the psychedelic context of the Dead’s formative years, coupled with the Ego Death principle that was a predominant force in the band’s personna and appeal, it’s clear that the meaning of this lyric is cryptic. It’s not the individual who must die, it is the Ego. This concept is a recurring theme of the Grateful Dead.

With this in mind, let’s reconsider the tautological nature of the term, Grateful Dead. There is no way to overstate our gratitude for the miraculous life with which we have been gifted. The fact that it will end someday – at least as we understand it in the present tense – does not diminish that gift. Rather, this knowledge serves to perfect the experience in that its temporary, short-lived nature makes it all the more precious. Ergo, we must be grateful for the fact that we will one day die, and allow the Ego Death that accompanies this principle to govern our behavior.

As Jerry put it in the film, “Long Strange Trip”: “For me it has a lot to do with getting out of the way, you know what I mean? At some point I decided not to be ‘me’ and to be ‘they.’ When it’s something more than my own little self, that’s it! That’s the goal.”

There is a profound sense of humility in this statement, as in the tautological nature of the name, Grateful Dead. In both we confront the fundamental question: Do we spend our limited time in this life focused on ourselves as individuals, fearing and avoiding death, and acting out of Ego, entitlement and privilege? Or do we accept and confront death in a way that enables us to live joyfully, in peace, and in harmony with the billions of other beings – human and otherwise – with whom we share this planet?

Concert of the week in Grateful Dead history: February 27, 1969 (Listen Now)

Want to find out about future concerts of the week?