Concert of the week in Grateful Dead history: July 8, 1978 (Listen Now)

Sometimes we live no particular way but our own;

Sometimes we visit your country and live in your home.

By The Deadhead Cyclist

For Week

28

When a band has played more than 2300 shows, it’s hard to imagine that any one of them would achieve legendary status. But certain Grateful Dead concerts firmly fit into that category. For starters, there’s little disagreement that 5/8/77 at Cornell University’s Barton Hall would make the list; the 12/31/78 Closing of Winterland comes to mind; 2/27/69 at the Fillmore West – from which the epic, Side 1-long Dark Star on the Live Dead album was derived – would have to be included; the Great American Music Hall show on 8/13/75 is an obvious choice; 5/26/72 at London’s Lyceum Theater, the final date of the Europe ’72 tour, has been immortalized on the album of the same name; and more recently, the 12/15/86 show at the Oakland Coliseum arena – the Dead’s first performance in more than five months after Jerry Garcia collapsed in a diabetic coma on July 10th of that year and almost died – easily deserves such distinction.

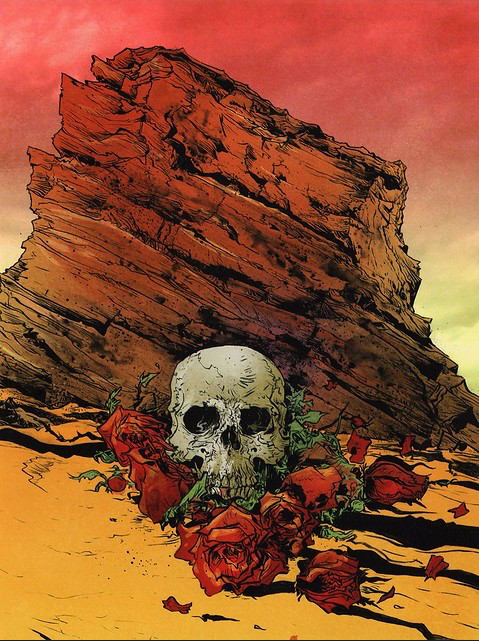

T.W.I.G.D.H. features a concert that’s often mentioned among Deadheads as one of the group’s best of all time: 7/8/78 at Red Rocks Amphitheater in Morrison, Colorado, a tiny town (population: 428) with a rich history, made even richer by the opening of Red Rocks in June, 1941. The July 8th show was the second of a two-night stand that was the Dead’s Red Rocks debut, and the venue immediately became one of their favorite places to perform. The band returned for two more shows in August of the same year, and played Red Rocks 20 times between 1978 and 1987. Having been to Red Rocks many times since moving to Colorado in ’92 (but, regrettably, never seeing the Grateful Dead there), I can state with some authority that it is one of the best outdoor concert venues in the world.

The second set of the 7/8/78 show is truly epic, highlighted by a 78-minute, non-stop musical odyssey: Estimated Prophet>The Other One>Eyes of the World>Drums>Space>Wharf Rat>Franklin’s Tower>Sugar Magnolia. While listening to this show during a recent ride, I was struck by the phrase, “Sometimes we live no particular way but our own,” in a way that hadn’t occurred to me previously. These words bear unexpected fruit upon deeper examination.

No matter the setting, our experience at any given moment is potentially affected by those around us. Literally and poetically, our fellow Earthlings inevitably move at a pace that is either slower or faster than “our own.” This can be challenging, depending on if and how we choose to react. There are several possibilities, all within our control if we choose to exercise it.

For example, as a cyclist, I try to get into a groove that suits my riding style and the terrain passing beneath my wheels. There’s a “sweet spot” where all of the variables – the grade, my gear selection, the temperature, the wind, the strength of my stroke – all work together most efficiently. At that moment, I am riding “no particular way but my own.” But let’s say that suddenly I find myself approaching another cyclist from behind who is riding at a pace slower than mine. Now what?

Eventually, I’m going to have to pass the slower rider, so I have two primary choices: 1. Continue at the same speed until I reach the other cyclist, which might force me to ride at the other cyclist’s pace until I can safely pass. 2. Increase my pace and try to synchronize passing with the next convenient break in traffic. In either case, I’m no longer riding at my preferred pace but, rather, must alter my pace to adjust to the speed of the other rider. Deadaphorically, I am temporarily visiting the country and living in the home of my fellow cyclist. This shift is necessary, given that I am sharing the road, as we all do within the contexts of our various pursuits.

As social beings, we are continually confronted with those moving at various paces relative to our own. And it is our choice whether to allow this dynamic to cause us to alter our own pace.

Conversely, if a cyclist riding at a faster pace approaches me from behind and passes me, I also have two choices. 1. Continue at the same pace. 2. Allow the fact that I have been passed to cause me to speed up. Why on Earth, you might ask, would anyone choose #2? There are two answers. The first is that my ego is bruised by having been passed, obviously a bad reason, but it happens, and I’ve been guilty of it. Sometimes – and this is particularly true of athletic pursuits – our competitive drive takes over and rules the day.

The second answer is much more interesting. Being passed by someone going faster could inspire you to strive harder in the direction of your goals, as it reveals what is possible. To illustrate this point, we’ll travel back to the mid-Twentieth Century.

Prior to 1954 it was considered physically impossible for a human being to run a mile in less than four minutes. Many elite athletes had tried and not one had succeeded. But on May 6, 1954 at the Iffley Road Track at Oxford University, an English physician and academic named Roger Bannister became the first individual to break the four-minute-mile barrier with a time of three minutes and 59.4 seconds. Less than two months later, on June 21st, an Australian runner named John Landy became the second human to break the four-minute-mile barrier at an international track meet at Turku, Finland. The word was out that it was, indeed, possible to run a mile in less than four minutes, and the very belief in that possibility forever altered the parameters that had previously existed within the sport. Within the ensuing five years, Landy was just the first of twenty-one individuals to follow in Bannister’s footsteps (pun intended) and break the four-minute-mile barrier!

Whether or not Robert Hunter had these dynamics in mind when he wrote the lyrics to Eyes of the World, the lesson is clear: As social beings, we are continually confronted with those moving at various paces relative to our own. It’s our choice whether to allow this dynamic to influence us to change our own pace. Sometimes we simply continue to “live no particular way but our own”; Sometimes we observe and emulate the lives of others.

Keep in mind, though, that these two approaches are not mutually exclusive. It’s possible to be inspired by what we observe in others and integrate their influences, while still remaining true to ourselves. The key is to be sure we are making a conscious choice, rather than being reactive. This way, the “songs that we sing” can become “songs of our own,” even if someone else sang it first. You never know when your new song might be the thrill of a lifetime as you become the second human being to break the four-minute mile barrier!

Concert of the week in Grateful Dead history: July 8, 1978 (Listen Now)

Subscribe and stay in touch.